Written by Gail Corey Tabernacle Historical Society

Abstract

In 2023, the Tabernacle Historical Society initiated Remember the Forgotten, a project to document the history of African Americans in Tabernacle New Jersey, with a focus on those buried at the African Methodist Episcopal Cemetery (AME), on Carranza Road. A Ground Penetrating Radar survey verified the presence of unmarked graves. We contacted descendants of known gravesites to locate ancestors who also may be buried there. We were able to confirm the existence of the original trustees of the property, and we were successful in a genealogical study of one of the trustees, a Civil War Veteran. We also found connections between indigenous people and some of their descendants. Furthermore, we discovered other historic Black churches, that served as a central part of life and identity for many in the community. The valuable friendships formed with members of the Friendship AME Church in Browns Mills have been an unexpected, joyous outcome.

Introduction

Purpose

The Tabernacle Historical Society (Historical Society of Tabernacle) received a grant from the New Jersey Council for the Humanities in December 2023. The grant funded the project, “Remember the Forgotten,” to document the history of African Americans who resided in Tabernacle New Jersey, especially their contributions to our community, and to ensure the forgotten African Americans buried at the AME Cemetery are remembered. This paper summarizes the initial results.

Background

Cemeteries provide a window into the past. They contribute to a community’s history and teach us what came before, so we can forge a better future. On October 13, 1868, 1.9 acres in Shamong Twp. sold for $15. The buyers comprised Trustees of a new African Methodist Episcopal local congregation. The deed states “… come to be erected and built thereon a house of worship for the use of the members of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and a part of same shall be used as a burial ground.” 1. Nothing is known about the African American population in Tabernacle beyond the existence of the African Methodist Episcopal Cemetery, a resting ground for freed and formerly enslaved people, and census records.

In the 2020 article “African American Cemeteries and the Restoration Movement · Brooklyn Cemetery Project” the authors claim that most “Black cemeteries were not delineated by deeds or legal instruments.” 2 A deed was issued for the sale of 1.9 acres, in now Tabernacle Township, to a Black farmer and his wife, John and Mary Ann Gray in 1868. John Gray deeded this property to the AME Church for a church & burial ground. Including Gray, the other trustees for the property were George Eares, David Thompson and Stacey Mires. A copy of the original deed is in possession of the Tabernacle Historical Society. The Burlington County Clerk’s Office has copies of earlier deeds, one of which is from 1865 which states that Adision White sold land to Wesley Decou. The other deed, 1868, records that David Decou sells the land to John Gray.

In 1910 the edifice housed the Free Christian Zion Church. The building remained standing which stood until 1935. The only surviving church remnant is its foundation. Figures 1 and 2 are

a copy of the 1870 deed. Figure 3 is a map detail showing church and cemetery in the 1938 WPA Veterans Grave Registration project, as well as the burial site of Civil War Veteran George Eares and the church’s foundation. 3 Today there is nothing to suggest the former existence of the Church other than a small rock pile, however the cemetery is still in use.

Courtesy of Tabernacle Historical Society.

Many slaves and former slaves would scratch codes on rocks to designate a burial site or place a simple wooden cross that would disintegrate over time. Although no written records have been located from the late 1800s to early 1900s to document burials, there are many grave markers from the latter half of the 1900s. More than 50 of those grave markers remain visible. The last burial occurred in June 2021. The deceased, age 99, had told her family that “it was a cemetery where black families could bury their deceased for free, i.e.,” they did not have to pay for a plot. It was her wish to be buried in this sacred ground.

There has been speculation regarding Black settlements in the area during the 1800s. We believe that Black settlements may have existed as ephemeral camps, which were used to create coal/fuel from the chopping of tree stumps. George D. Flemming suggests in his book, Brotherton: New Jersey’s First and Only Indian Reservation and the Communities of Shamong and Tabernacle That Followed, that Native Americans worked at the forges and sawmills in Atsion, Shamong Township. 4 Is it possible that these ephemeral camps originated to provide workmen for these forges and sawmills? Further investigation is needed to answer this question. Figure 4 shows an 1856 map of Shamong Township, Tabernacle does not appear, as it was part of Shamong at the time. 5 However Figure 5 shows an 1859 map with Tabernacle. 6

Figure 5

Our project team draws from the talents of individuals from varied backgrounds. Mr. Richard Franzen, President and historian of Tabernacle Historical Society (THS), provided valuable information on Tabernacle history, its inhabitants and historic sites. Gail Corey (THS), former school administrator, served as project director/coordinator. Denise Hudson (THS), genealogist, was responsible for tracing the genealogies of those buried in the cemetery and locating descendants. Donna Hayes, Associate Pastor for Friendship AME Church Browns Mills, and Carlotta Powell – Friendship AME Church Browns Mills, researched AME Church history and investigated the Free Zion Christian Church of Christ supplanting the AME church in Tabernacle. Funmi Adebajo and Touba Marrie, both graduate students at Rutgers University, served as interns. They provided valuable assistance locating descendants. Funmi was able to obtain oral interviews for 6 families and Touba worked with Rev. Donna Hayes and Carlotta Powell to locate descendants. Doreen Bloomer, President of Hudson County Genealogy Board, offered her assistance as a consultant.

Taylor Brookins, National Park Service, a Historian for the Northeast Regional Office of History and Preservation Assistance, recently published in the Journal of the African American Genealogy and Historical Society on the Free Black Community of antebellum Delaware. In her paper, shedescribesagroup of former escaped slavesthatshe calls Maroons, who ran to remote areas and forested areas. There, they established their own communities and acquired land, and as their communities grew, they built schools. Some of the communities participated in underground railroad activities. 7 There is no evidence that the land surrounding the AME Church and Cemetery on Carranza Road, Tabernacle, served as a Maroon community. The suggestion, however, provides consideration for future research. Descendant interviews from individuals buried in the AME Cemetery talk about a black hamlet that was present in Tabernacle on Flyatt Road in the mid-1900s. This hamlet is not the same as the ephemeral camps previously mentioned.

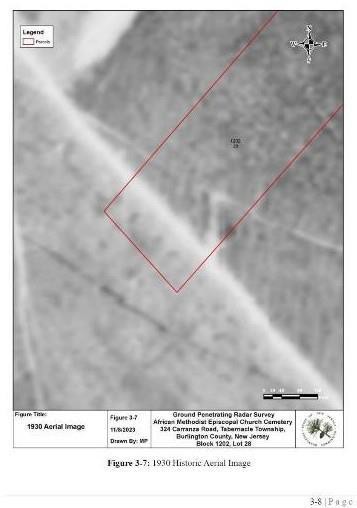

Methods

Ground Penetrating Radar, documentary research, maps, genealogies, oral histories and photographs were used to trace the history of African Americans in Tabernacle. Our research began with a Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) survey that was conducted in 2023 by the New Jersey Pinelands Commission. We anticipated the survey’s results would verify the presence of burial sites in the AME Cemetery on Carranza Road in Tabernacle, Burlington County, situated on Tax Block 1202, Lot 28 at 324 Carranza Road. The areas’ flora includes pines and oaks. Figure 6 shows a 1930 aerial of the GPR project location map; Figure 7 is the Topo of the project location map.

Courtesy of Marc Paalast, NJ Pinelands Commission

The surveyor determined that the most advantageous survey method would be to

run a baseline along the edge of the property, at the boundaries of Block 1202, Lots 28 and 32, perpendicular to Carranza Road. They performed the survey along two-foot interval transects running parallel to Carranza Road. Without knowing the original burial’s orientation, the surveyor assumed that later burials would match the pattern of existing burials that remain visible. He determined “if the original burials were oriented east-west, as is traditional for Christian burials, then this method would cross diagonally along their long axis and the graves would still likely be visible in multiple GPR transects spaced two feet apart.” 8 The GPR equipment recorded all identified anomalies on a spreadsheet. which is available in the NJ Pinelands Commission report.

Because the THS records do not record burials more than 50 or so years ago, we decided to work backwards by contacting descendants of known gravesites to locate the ancestors of those buried prior to the 1900s. Locating missing records proved to be a challenge. Using census records, we

searched for the trustees whom the cemetery property was deeded. We reviewed relevant published literature and documents, and we interviewed descendants of those buried in the cemetery to compile an oral history of Tabernacle’s African American community.

Results

Ground Penetrating Radar Survey

The GPR survey noted the current cemetery property is over 9 acres in size, whereas the deed states the acquired land only comprised 1.9 acres. The 1930 aerial map shows that the church and burials are located within 1.9 acre lot section. The report suggests the property may not have been officially subdivided, or the property may have been combined with other lots later. The report also identifies standing headstones and other grave markers present toward the rear of the lot’s landscaped area. Some slight ground depressions were observed in this area, possibly due to collapsed coffins.9

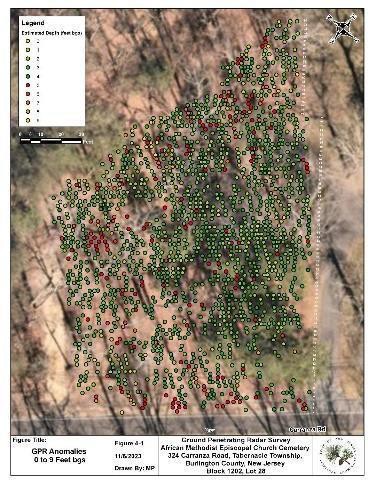

Figure 8 shows each of the anomalies occurring within 9.5 feet of the ground surface. Figure 9 shows the anomalies within 9.5 feet of the ground surface in 1-foot depth slices.

Courtesy of Marc Paalast, NJ Pinelands Commission

The GPR survey identified at least 757 anomalies within 2.5 feet below grade. However, anomalies between 2.5 and 9.5 feet hold the most potential to be associated with burial remains. The survey

recorded 31 anomalies over 9.5 feet below the ground surface. Anomalies between the depths of 6.5 feet and 9.5 feet were recorded in the area where known burials exist, one of which stood out as a potential unmarked grave. The only evidence for the church’s location is a small ironstone rubble pile. Because this site contained no trees it probably denotes where the building once stood, which would agree with the 1930 aerial photograph depicting the church. Figures 10 and 11 show the building standing on stone piers that likely featured ironstone construction, hence, the rubble pile with ironstone.

Courtesy of Marc Paalast, NJ Pinelands Commission

Historical Research

Robert Keith Collins writes in Sage Journal 2020 , How Africans Met Native Americans during Slavery, “In New Jersey, in the mid-18th century enslaved Africans were characterized as having a distinct phenotype due to extensive intermarriage with Native Americans of the colony.” 10

Based on the research of George D. Flemming 11 ,12 and the Rev. Dr. John Norwood 13 information is available on the Brotherton Reservation in Indian Mills (Shamong Township) and New Jersey’s Nanticoke and Lenape Indians. Norwood writes about the long history of racial misidentification of Indians. He writes, “who remained on the east seaboard were called

“Mulatto” or “Free Person of Color….” Note that the term “mulatto” had different connotations over the years. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines “mulatto” as a person of mixed white and Black ancestry. Prior to Tabernacle being legislatively incorporated as a separate municipality in 1901, the town existed within Shamong Township (Indian Mills). The Brotherton Reservation (no longer in existence) in Indian Mills was once located four miles southwest of Tabernacle. George Eares’s descendants, claim to have Native American or indigenous peoples heritage, which will be discussed in the oral histories section. “Indian Ann” Ashatama Roberts of New Jersey, the daughter of Elisha Ashatama, a Brotherton Indian married a black freeman, John Roberts. In addition to this, the 1880 decennial census identifies John Gray, an original trustee in the 1868 cemetery property deed, as mulatto. The same census also records his, wife Mary Ann Gray as mulatto. Some sources suggest that she was half African American and half indigenous people.

Church Research and Cemetery Ownership

The first institutions African Americans founded after the Civil War included cemeteries, churches, and schools. Nadia Orton in “Recovering and Preserving African American Cemeteries

| National Trust for Historic Preservation (savingplaces.org) “discusses the risk that these sites might become lost due to development, neglect and abandonment.14 The AME cemetery in Tabernacle fortunately still exists. A family member of relatives buried there continues to

maintain the burial ground. A photograph showing the cemetery and the Marker located at the site appears in Figures 12 and 13.

Courtesy of Tabernacle Historical Society

Tracing the history of the African Methodist Episcopal Church built within the cemetery is an important aspect of this project. There are several references claiming that Ann Ashatama, known as “Indian Ann” and her husband, John Roberts, a former slave, established the church. In Ernest Lyght’s book, The Path of Freedom- The Black Presence In New Jersey’s Burlington County 1659-1900,15 located on Carranza Road in Tabernacle was known as the A.M.E. Church at Dingletown. Dingletown was a local name for the site of “Indian” Ann’s cabin on Dingletown Road, south of the village of Tabernacle. The word “dingle” means “shady dell.” Today, tall trees keep the area well shaded. Lyght also states that Ann and John founded the church.12 George Flemming states: “A frame church that once stood on the Great Road to Little Egg Harbor (now Carranza Road) was founded, in part, by Ann Roberts in the mid to late 1800s.” Abandoned and deteriorating the church underwent demolition in 1935.” 16

Additional information can be found on the Historical Society of Indian Mills website: “Ann Ashatama married a Black man from Virginia named John Roberts. Together, John and Ann raised seven children. They lived in a small one room log cabin on the west side of Dingletown Road (now Forked Neck Road) in a small hamlet known as Dingletown. Ann and her husband were instrumental in the founding of an African Methodist-Episcopal Church on Carranza Road. Her husband John Roberts died young, in the Burlington County Alms House, New Lisbon New Jersey in 1852.” 17 The claim that Ann and her husband John Roberts founded the AME church appears in several secondary resources. This assertion, however, contradicts the documentation found on the church property. Tax records show that First Baptist Tabernacle, a Black Baptist church postal address 141 Flyatt, Tabernacle New Jersey owns Block 1202 Lot 28 Block 1001 Lot 17. Did the Church take over ownership of the cemetery or does it just own specific burial lots? The Tax map identifies the 8.8 – acre parcel as “Exempted Charitable property.” Although ownership of the AME cemetery remains unclear, we do know, according to Paul W. Schopp, Assistant Director, South Jersey Culture & History Center Stockton University, that the African Methodist Episcopal Church, as a denomination, is a connectional church and holds all local churches and property in trust for the denomination, similar to the United Methodist Church denomination. This means that the AME Churches, New Jersey annual conference and the general conference still retain ownership of the burial ground and adjacent property, totally almost 9 acres of land, based on the Tabernacle Tax Maps (8.8 acres, Block 12, lot 28). 19

In 1867, Jacob’s Chapel was built as an African Methodist Episcopal Church in what is now Mount Laurel New Jersey. The deed for the Colemantown Negro cemetery established in 1858 permitted an AME edifice to be constructed within the cemetery’s confines. Three of the four trustees who received

the deed for the Carranza Road AME cemetery/church in 1868 are buried in Jacob’s Chapel, Mt. Laurel – Stacy Miers, John Gray and David Thompson.

Figure 14 is a photograph of the tombstone of Mary Ann Gray at Jacob’s Chapel.

Morgan’s History of the New Jersey AME Conference also served as a resource to gather historical information on the church. It contains the conference minutes during the late1800s. A review of the conference minutes from 1870 to 1884 provides a mention of an AME church in Shamong that appeared on the list of circuit visits in 1872. 20 We assume this is the AME church/cemetery in Tabernacle, which was part of Shamong at that time.

Courtesy of Carlotta Powell, Friendship AME Church Browns Mill, NJ

Other defunct American Churches in Tabernacle include the Free Christian Zion Church of Christ, which congregation worshipped in the former AME Church on Carranza Road. The only documented record we have of its existence is in the Directory of Churches in New Jersey, Vol III Burlington County Historical Records Works Project Administration, 1940. We believe the

AME Church became the Free Zion Christian in 1910; however, we have been unable to confirm the accurate date on the founding of this church. 21

The Chamber family is believed to have founded the First Tabernacle Baptist Church on Flyatt Road after World War II. Family members lie in repose within the AME cemetery. James Cosby served as the church’s first minister. He also lies buried in the AME cemetery. To date, we have been unsuccessful in locating any living relatives of James Cosby. The Church closed and eventually became overgrown by weeds after the members of the church died, but the signage remains. Other than the images below, Figures 15-16, we have no further information on the church.

Courtesy of Tabernacle Historical Society

Albert and Katie Patterson, who initially lived in Burlington, New Jersey, founded The Temple of God Holiness Church, where they ran a tent church. In 1947, however they relocated to Tuckerton Road after purchasing three one-half acres of land. Albert personally built their home and a church on this land, which would become the Temple of God Holiness Church. Albert and Katie were devout Christians, with Albert being ordained as a Reverend and Katie as a Bishop.

Their church on Tuckerton Road served as a cornerstone for the community, especially for African American families in Tabernacle and Indian Mills. The Church was known for its close- knit community, deep spiritual commitment, and unique Pentecostal practices, including extended revivals, foot-washing ceremonies, and nighttime funerals.

These various congregations, although no longer exist, demonstrate the strong roll they played in the African American population and their religious contribution to the Tabernacle community.

Summary of Oral Histories

The following paragraphs are excerpts from oral history interviews conducted for this project.

Cook Family: Goldie Elizabeth Cook was born to Reverend Albert and Katie Patterson in

Waterview, Virginia, Middlesex County, on July 11, 1921. She had several siblings: George Patterson, Alfred Patterson, Helen Murray, Thelma Cannon, and Evelyn Wilson. Her parents also adopted two children, Richard Dean and Anita Bryant. The family moved to Burlington County New Jersey when Goldie was a small child and eventually settled permanently in Indian Mills. As an adult, Goldie worked for General Motors in Trenton, in the Cathedral in The Woods

Church in Medford Lakes, and for many local families, tending to their homes and children. In her spare time, Goldie worked on local farms picking seasonal crops and then canning them.

Goldie’s parents, Reverend Albert and Katie Patterson, were ministers who founded the Temple of God Holiness Church in Indian Mills. Goldie dedicated much time to helping run and beautify the church. She loved the Lord, gospel music, and helping others. Her favourite song was “I Won’t Complain.” Despite her large heart, she was a feisty lady who could stand her ground when necessary. In her free time, she enjoyed fishing, cooking, and hosting barbecues. Goldie

married Mr. Dallas Cook and with the fruits of her labour, she built a home in Tabernacle in

1969 where she lived with her husband.

Dallas Cook passed away in July 1974. Little is known about his side of the family, but he was the only father Alfred (Goldie’s son) ever knew. Dallas suffered from epileptic seizures and, although he and Goldie divorced at some point in their marriage, they continued to live together due to his poor health until his death. Goldie later passed away peacefully at her home in Tabernacle, NJ, on June 12, 2021, at the age of 99, just one month shy of her 100th birthday.

Dallas and Goldie Cook are survived by 21 great-grandchildren and 33 great-great-

grandchildren. A picture of Dallas Cook’s gravesite appears below, Figure 17.

Courtesy of Tabernacle Historical Society

Patterson Family: Alfred David Patterson was married to Mary (May) Thompson Patterson, who

was born in South Carolina (Figures 18-19). Alfred was a trucker who travelled a lot. He met Mary in South Carolina and brought her to New Jersey to live with his mother, Goldie. Together, Alfred and Mary had eight children in quick succession. Mary died at 78 years old in 2013. Due to Alfred’s constant trips, it was hard for Mary to take care of the eight children alone, so Goldie’s house became the home base for Alfred’s family, with several grandchildren living with her at any given

time. Mary had to do domestic chores to earn money, but Goldie was very helpful in raising the kids. Alfred David Patterson died in 2012 in North Carolina at the age of 69.

Figure 19

Courtesy of Laurie Patterson.

Mike Patterson was the eldest son of Alfred, born on July 9, 1958. He had eight siblings: Larry Patterson, Goldie Patterson (deceased in her twenties), Carol Browning (deceased), Patricia Patterson (deceased), David Patterson, Eugene Patterson, and Diana Patterson. Mike and Laurie Patterson were married on August 21, 1987. Mike had a child from a previous relationship, and together, they have two children. Laurie studied criminal justice and worked for the New Jersey State Parole Board for 35 years, while Mike worked as a construction worker. Both are retired and live in the Goldie Patterson family house. Mike and Laurie moved to Tabernacle in April 1992 when Goldie Cook was old and needed someone to take over the Goldie Patterson house. At that time, the community was predominantly white with a small group of Black residents living on Flyatt Road. Mike and his adopted uncle Richard are committed to the upkeep of the Tabernacle Cemetery. He lives with his wife Laurie in Tabernacle New Jersey as one of the very few

descendants of the original settlers of the community. Michael and Richard appear below. (Figure 20)

Courtesy of Laurie Patterson.

Imes Family: Hezekiah Imes, (Figure 21) originally from Ivanhoe, North Carolina, and Helen Lee Imes (Nee Durham), (Figure 22) from Abington, Pennsylvania, were farm laborers who met and married on May 20, 1947. Helen and Hezekiah settled in Indian Mills, next to Tabernacle and had eight children: Diane (1948), Carolyn (1952), Rudy, Patricia (1953), Sandy (1957), Jeffrey

and Michael (1959), and Denise (1962).

The family lived first on Tuckerton Road before finally moving to Flyatt Road in 1981. At the time the Imes family lived on Tuckerton Road, about four Black families also lived there. This included the Laws family and the Patterson families. In contrast, there were no white people on Flyatt Road. The tight-knit Black community in Indian Mills, comprised of about 300 to 400 people, created a strong support network for one another. Helen Imes recalls facing significant racism, and the children were taught to be cautious. The children stayed in their area, where they felt familiar and safe, avoiding the main roads due to the presence of many white families. The Imes children often visited other Black families on Tuckerton Road, such as the Pattersons and Joneses, using the paths and back-roads. They regularly attended services at the Holiness Church, founded by Rev. Albert Patterson, which was located just a quarter mile from their home.

Helen was of Native American descent, with roots in both the Cherokee and Blackfoot tribes, specifically from the Cherokee/Nzitapi Ani Giduhwa community. She came from a lineage of migrant workers. Her grandfather was from North Carolina, and they had extended family in Long Island New York. In addition to her biological children, Helen raised her granddaughter- Tamika Imes, daughter of Carolyn Imes. Tamika was handed to her Helen when she was just a few weeks old, after being born prematurely at 2lbs 11oz. Her birth was reported by the Philadelphia Inquirer as the smallest surviving baby in 1971.

There are nine unmarked graves belonging to the Imes family at the Tabernacle Cemetery (Figure 23) Patricia Imes suffered seven miscarriages between her first and last children, Tamika and Terrence. Each of these seven children was stillborn. Caroline Imes, Patricia Imes’

sister also had two male children buried there; one was stillborn, and the other lived only a few hours before passing away. The section of the cemetery which included the babies’ graves was damaged by weather over time. Someone removed the headstones and placards from the graves and placed them under a tree.

Denise Hudson Curtesy of Tabernacle Historical Society

Hezekiah Imes worked on the farms and trained some of the best horses. His children remember him as a hard worker. Hezekiah worked for Everett Abrams, one of the Abrams brothers who owned large farmlands of tomatoes and corn in Indian Mills. He continued working for Abrams until 1973. He also worked at the Indian Mills Stock farm, for a man called Roland. He augmented his farm work by driving trucks for Campbell Soup but as with other Black employees then, he was treated poorly at work and his wages from truck driving could barely purchase a week’s worth of food for the family from the deli. However, the farm work sustained the family as Hezekiah often brought home 50lb sacks of potatoes from the farm in winter which he shared with friends and family. The community practiced sharecropping and in the different harvest seasons, the children would join Helen when she worked on the Abrahams farm to harvest broccoli and blueberries to supplement the family’s income. The family made do with

what they had, often relying on simple meals like potatoes, and sometimes only having one meal a day.

Styles Family: Reid O. Styles Sr. was born on May 24th, 1896, in Lexington, Virginia, to Harry and Virginia Styles. He left Lexington for Pittsburgh Pennsylvania, where he met and married Catherine Charles on November 9, 1914. He moved to Philadelphia. The marriage produced five daughters. He met and later married Margaret Davis from Philadelphia, Pa., in 1947, and from this union produced four boys. Reid, Jr., William, Harry, and Dennis. Reid Styles was a committed member of Baptist Church of Tabernacle and later he worshipped at the Antioch Christian Church, Chesilhurst, New Jersey. He was later ordained as a deacon in 1978 at Mt.

Zion Baptist Church. He served there till his passing. Reid was considered a unique individual and highly skilled with the use of his hands. Though Tabernacle was predominantly a white town, Flyatt road was mostly Black people. Flyatt Road could have been named Styles Road as Reid Styles owned 76 acres of land there, which he sold exclusively to Black individuals. He also owned land at Medford Lakes Road and Indian Mills, which included the property the Imes Family lived on. This earned him respect from both his Black and white neighbours. Reid’s efforts in building his community were notable. He built his own home and helped others with theirs, doing everything except the electrical work. He was a man given to knowledge, always figured out how to solve complex problems, and was a great conversationalist. This earned him respect from both the Black and white folks in Tabernacle. The white neighbours would visit him, spending hours discussing and giving him things that he could use for the building construction projects he was working on. The African Americans also respected him and went out of their way to help him.

When Reid Styles first son Reid Jr was graduating from High school in 1966 there were only a few African Americans in the school, where they all got a good education. Only 4 of the 43 graduating students at Tabernacle Elementary School in the school were Black people. Reid Jr. was also the president of his eighth grade class which was very unusual. The Black people were survivors in an environment that was not necessarily as hospitable as they wanted but the Black community learned to adapt.

Reid was concerned about the treatment of women, so he was protective of his daughters’ well- being and future. Though he sold most of his land, he ensured each of his daughters received an acre next to the family home and helped to build their houses. However, his sons did not receive any property; Dennis, one of his sons, currently lives as the only original dweller in Flyatt Road in Tabernacle, but he had to buy the property from one of the people his father Reid, had sold it to. Three of Reid’s four sons are still alive, while William Styles passed away on October 4th, 2017. Dennis Styles remains the only original resident on Flyatt Road. Today, most of the original Tabernacle residents have either passed away or relocated, and many properties have been taken over by the township due to unpaid taxes. Figures 24 and 25 are of the tombstones of Reid (left) and Margaret Styles.

Eayers Family: The most noted resident of the AME cemetery is George Eayers (Eares, Ayers). George Eayres was born in 1830 and lived in Burlington County, New Jersey. He married Lucretia Earyes on October 25, 1855, in Philadelphia, and together they had three children: Edward (born 1891), George Jr. (born 1864), and Rachel (born 1868). The family surname, Earyes, appeared in various forms over time, including Eares, Eyers, and Ayers. George worked as a farmer and laborer before volunteering for military service during the Civil War. On January 23, 1864, he enlisted as a private in the 25th Regiment of the U.S. Colored Troops. He was posted to Fort Pickens, Florida, and served until his discharge on December 6, 1865.

Military records describe him as 5’5″ tall, with dark hair and dark eyes. George suffered a back injury while moving a large cannon during his service. His pension application detailed that he was crushed under an overweight timber while helping to move a large cannon, permanently damaging his back. However, the injury was not documented in his regiment’s rolls, which hindered his efforts to secure an valid pension. Despite affidavits from colleagues, neighbours, and Isaac Ashton his daughter’s father-in-law, his claim was denied because his disability “was not found to be of pensionable degree” and due to insufficient medical evidence, such as the name of the surgeon that treated him. George Eares tombstone appears below in Figure 26.

Courtesy of Tabernacle Historical Society

Among his children was a daughter named Racheal Eayres, born in 1868. Racheal married George Ashton, and together they had a daughter, Edna Ashton, who was born in 1895. She was married to John Farrel and together, they had five children, their first daughter, Eileen Farrel Barnes was born in 1917. Tragically, Edna died in 1925 when Eileen was just eight years old.

Although some documents, like census records and pension applications, identified George Earyes as Black, other records, including his membership in the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), a group that typically excluded Black soldiers, suggested a different identity. Steven Thomas, a Civil War re-enactor, historical interpreter, and descendant of George Eares, confirms that George Eares would not have been accepted into the GAR as a Black soldier. This ambiguity in his

identity reflects the historical context where Native Americans often concealed their identities, sometimes presenting as Black to navigate the social and racial dynamics of the time.

The family’s roots in Burlington New Jersey, also hint at deeper connections to the area’s Native American history. The Earyes family lived in Shamong, a settlement founded by someone named Earyes. Also, an adjacent town, Earyestown Lumberton New Jersey, was established by an English family named Earyes, known to have owned slaves. This history suggests that George Eares may have been a descendant of these enslaved people. Kim Pearson, descendant of George Eares, contacted Reverend Dr. John Norwood, a prominent representative and advisor for the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Tribal Nation in New Jerseys and discovered he has some documentation of the Ashton family, (Rachel Earyes in-laws), suggesting possible links to the indigenous community forced out of Indian reservations in the 1880s. In his communication with Kim Pearson, Reverend Norwood also said that two of his own ancestors served in the same USCT regiment with George Eares. 22 Based on stories told by Eileen Barnes, great- granddaughter of George Eares, it is the family’s understanding that everyone in her lineage was Native American. Figures 27 and 28 are of Eileen Barnes (left) and Edna Ashton Farrel, granddaughter of George Earyes (right).

Courtesy of Kim Pearson descendant

After Edna died, John Farrell remarried and had another child. Although John Farrell reportedly took more pride in his sons, it was Eileen and her sisters who cared for him in his later years. After her mother’s death, Eileen lived for some time with her grandfather George Aston- who became a prominent figure in her life. She attended powwows as a child and passed her family’s rich history to her children about their ancestral roots. Eileen mentioned that her mother, Edna Ashton, was a full-blooded Native American and that her grandfather, George Ashton, was not only a Native American but potentially a chief. He identified as Algonquin, part of the Lenni- Lenape Native American groups that lived in Pennsylvania and surrounding areas before European settlement.

Eileen Barnes married a soldier, and together they had five children. In 1946, her husband died in a VA hospital in Philadelphia from a mysterious illness. Eileen became the family matriarch, dedicating her life to raising her children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, and great-great- grandchildren. Her faith became the cornerstone of her life, and she worked tirelessly to pass that faith on to her descendants. Eileen is fondly remembered for her large family meals on Sundays and holidays, her skills as a church organist, and her poetry. Eileen Farrel Barnes passed away in 1998 and was laid to rest alongside her mother Edna Ashton Farrel, and her grandparents George and Racheal Ashton on family plots at the Atco Cemetery in Camden County. Her daughter, Ann Barnes was also buried there. Below is a picture of Steve Thomas ( Figure 29), descendant of George Eares (Earyes). Steve was a participant and played the flute at a Tabernacle History Society event to honor Civil War Veterans.

Figure 29

Courtesy of Albert J. Countryman Jr. Pineland Sun Nov 6-12, 2024

DISCUSSION

Project Challenges and Next Steps: Locating missing records has been a major challenge to this project. AME churches were formed in Burlington County pre- and post-Civil War, especially in Evesham Township.23 Tabernacle was once part of Lower Evesham Township but there is no mention of the AME church on Carranza Road, which was built in 1870 about 3 years after Jacob’s Chapel was built.

In our attempt to gather information on the Free Zion Christian Church we end up with more questions rather than answers. We have been unable to find any records on the name change from the AME Church to the Free Zion Christian Church. Five years after the African Methodist Episcopal was officially formed in 1816 in Philadelphia, the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church was officially formed in 1821 in New York City. Free Zion Christian churches included white membership.

Many of the individuals buried in the mid to late 1900s were buried out of the Carl Miller Funeral Home and Mathis Funeral Home both in Medford. The funeral homes have not responded to our

request. We did contact a grave digger for the May Funeral Home in Camden who did remember burying someone in the cemetery in 2021. We know that the last burial that took place at the AME cemetery was Goldie Cook in 2021. Family research was a challenge, especially with the misspelling of names. The spelling of George Eayers is a prime example. During the implementation many resources became available for further research. Contact was made with the Philadelphia Historical Society for African American churches for access to their achieves. The Plainfield Public Library on African American genealogy offers webinars with tips on how to locate records and conduct research.24 Contact was made with personnel at the Blockson Library at Temple to help with the research on the Zionist Baptist Church on Flyatt road. To date, there has been no follow- up. The Pinelands Commission’s GPR study has recommended that an archaeological investigation in the area of the original church building would be useful in confirming its exact location. 25 We will investigate this undertaking. We will continue our research to identify members of the early congregation and clergy. Because the GPR survey report could not verify that the cemetery, which sold as a 1.9-acre lot, may in fact be 8 acres, the surveyor suggests the property may not have been officially subdivided, or the property may have been combined with other lots later. Further deed research would be required to determine this.

Endnotes:

- Burlington County Clerk’s Office 1870 – Burlington County Deed Book C8 page 607

- Darrell Barrell, Zondria Bond, and Erika Massie, African American Cemeteries and the Restoration Movement, Brooklyn Cemetery Project 2020 https://digilab.libs.uga.edu/cemetery/exhibits/show/brooklyn/african-american-cemeteries

- 1938 Works Project Administration NJ State Archives 1938 map Tabernacle, NJ

- George D. Flemming Brotherton: New Jersey’s First and Only Indian Reservation and the Communities of Shamong ad Tabernacle That Followed. 2005 pages 112, 142. Plexus Publishing, Inc. Medford, New Jersey

- https://mapgeeks.org/1856-map-of-new- jersey.jpg

- Library of Congress-https://www.loc.gov/resource/g3813b.la000442/

- Taylor Brookins Free Black Community of Antebellum Delaware Journal of the African American Historical Genealogy Society Vol 42, 2024

- Mark Paalvast, MA Archeologist Cultural Resources Specialist; New Jersey Pinelands Commission 11/15/23 Ground Penetrating Radar Survey – African Methodist Episcopal Church Cemetery 324 Carranza Road, Tabernacle, NJ Block 1202 Lot 28, pages 5-8

- Ibid: pages 39-40

- Robert Keith Collins, How African Met Native Americans during Slavery. 2020 Sage Journals Volume 19, Issue 3 , https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504220950396

- George D. Flemming Brotherton: New Jersey’s First and Only Indian Reservation and the Communities of Shamong ad Tabernacle That Followed. 2005 pages 112, 142. Plexus Publishing, Inc. Medford, New Jersey

- Ibid

- John Norwood “The Genealogical Records of the Nanticoke Lenni-Lenape Indians, (Bridgeton, New Jersey)” in 2007

- Nadia K. Orton. Recovering and Preserving African American Cemeteries | National Trust for Historic Preservation (savingplaces.org)” 2016

- Ernest Lyght The Path of Freedom- The Black Presence In New Jersey’s Burlington County1859-1900 (p 70-71), published 1973.

- George D. Flemming Brotherton: New Jersey’s First and Only Indian Reservation and the Communities of Shamong ad Tabernacle That Followed. 2005 pages 112, 142. Plexus Publishing, Inc. Medford, New Jersey

- Indian Mills Historical Society, www.imhs.org

- https://www.njtaxrecords./r/141-flyatt-road-tabernacle-burlington-county-nj-property-tax- record-591443-sheet12

- Paul Schopp, National Register of Historic Places – Nomination for Colemantown Meeting House, Jacob’s Chapel, and the cemetery. U.S. Department of Interior and National Park Service, 2015

- MORGAN’S HISTORY OF THE NEW JERSEY AME CONFERENCE-

www.njstatelib.org/research_library/new_jersey.

- Directory of Churches in New Jersey Vol III Burlington County Historical Records Works Project Administration 1940

- Kim Pearson On Measuring the Presence of Absence; April 17, 2020, https://kimpearson.net/the-presence-of-absence/

- Paul Schopp, National Register of Historic Places – Nomination for Colemantown Meeting House, Jacob’s Chapel, and the cemetery. U.S. Department of Interior and National Park Service, 2015

- Plainfield Public Library on African American genealogy. The link for this recording A Myriad of Slavery databases is https://youtu.be/H6lzdwvik0c?si=qmc1eam4C91pFfQ4.

- Mark Paalvast, MA, Archeologist Cultural Resources Specialist; New Jersey Pinelands Commission 11/15/23 Ground Penetrating Radar Survey – African Methodist Episcopal Church Cemetery 324 Carranza Road, Tabernacle, NJ Block 1202 Lot 28: page 41

IMAGE ATTRIBUTION

Mark Paalvast, MA Archeologist Cultural Resources Specialist; New Jersey Pinelands Commission 11/15/23; Tabernacle Historical Society www.tabernaclehistoricalsociety.org; Albert J. Countryman Jr. Pineland Sun Nov 6-12, 2024 page; Oral Histories Photographs release forms of family members-Tabernacle Historical Society

ACKNOWLEDGES: Thank you to the project team who made this paper possible, Mr. Rick Franzen, Denise Hudson, Donna Hayes, Carlotta Powell, Funmi Adebajo and Touba Marrie Also, Mr. Wayne R. Ferren Jr., who assisted with edits and rewrites and Mr. Paul Schopp historian and scholar who provided valuable information on the history of African Americans in southern New Jersey.